Active Topics

Active Topics  Memberlist

Memberlist  Calendar

Calendar  Search

Search  |

Active Topics Active Topics  Memberlist Memberlist  Calendar Calendar  Search Search |

| |

|

|

| Author | Message |

|

poli

Senior Member

Joined: 03Apr2007 Online Status: Offline Posts: 462 |

Topic: Software Testing Life Cycle Topic: Software Testing Life CyclePosted: 05May2007 at 5:59am |

|

Software Testing Life Cycle:

The test development life cycle contains the following components: Requirements Use Case Document Test Plan Test Case Test Case execution Report Analysis Bug Analysis Bug Reporting Typical interaction scenario from a user's perspective for system requirements studies or testing. In other words, "an actual or realistic example scenario". A use case describes the use of a system from start to finish. Use cases focus attention on aspects of a system useful to people outside of the system itself.

A collection of possible scenarios between the system under discussion and external actors, characterized by the goal the primary actor has toward the system's declared responsibilities, showing how the primary actor's goal might be delivered or might fail. Use cases are goals (use cases and goals are used interchangeably) that are made up of scenarios. Scenarios consist of a sequence of steps to achieve the goal, each step in a scenario is a sub (or mini) goal of the use case. As such each sub goal represents either another use case (subordinate use case) or an autonomous action that is at the lowest level desired by our use case decomposition. This hierarchical relationship is needed to properly model the requirements of a system being developed. A complete use case analysis requires several levels. In addition the level at which the use case is operating at it is important to understand the scope it is addressing. The level and scope are important to assure that the language and granularity of scenario steps remain consistent within the use case. There are two scopes that use cases are written from: Strategic and System. There are also three levels: Summary, User and Sub-function. Scopes: Strategic and SystemStrategic Scope:

The goal (Use Case) is a strategic goal with respect to the system.

These goals are goals of value to the organization. The use case shows

how the system is used to benefit the organization.,/p>

These strategic use cases will eventually use some of the same lower

level (subordinate) use cases. Use cases at system scope are bounded by the system under development. The goals represent specific functionality required of the system. The majority of the use cases are at system scope. These use cases are often steps in strategic level use cases Levels: Summary Goal , User Goal and Sub-function.Sub-function Level Use Case: A sub goal or step is below the main level of interest to the user. Examples are "logging in" and "locate a device in a DB". Always at System Scope. User Level Use Case:This is the level of greatest interest. It represents a user task or elementary business process. A user level goal addresses the question "Does your job performance depend on how many of these you do in a day". For example "Create Site View" or "Create New Device" would be user level goals but "Log In to System" would not. Always at System Scope. Summary Level Use Case:Written for either strategic or system scope. They represent collections of User Level Goals. For example summary goal "Configure Data Base" might include as a step, user level goal "Add Device to database". Either at System of Strategic Scope. Test DocumentationTest documentation is a required tool for managing and maintaining the testing process. Documents produced by testers should answer the following questions:

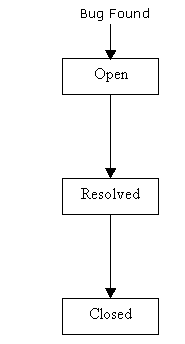

In entomology(the study of real, living Bugs), the term life cycle refers to the various stages that an insect assumes over its life. If you think back to your class, you will remember that the life cycle stages for most insects are the egg, larvae, pupae and adult. It seems appropriate, given that software problems are also called bugs, that a similar life cycle system is used to identify their stages of life. Figure 18.2 shows an example of the simplest, and most optimal, software bug life cycle.

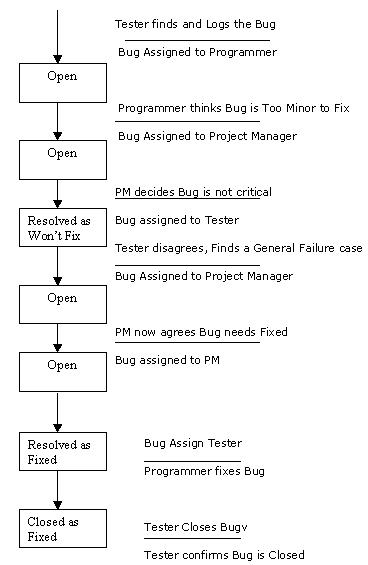

This example shows that when a bug is found by a Software Tester, its logged and assigned to a programmer to be fixed. This state is called open state. Once the programmer fixes the code , he assigns it back to the tester and the bugs enters the resolved state. The tester then performs a regression test to confirm that the bug is indeed fixed and, if it closes it out. The bug then enters its final state, the closed state. In some situations though, the life cycle gets a bit more complicated.In this case the life cycle starts out the same with the Tester opening the bug and assigning to the programmer, but the programmer doesn’t fix it. He doesn’t think its bad enough to fix and assigns it to the project manager to decide. The Project Manager agrees with the Programmer and places the Bug in the resolved state as a “wont-fix” bug. The tester disagrees, looks for and finds a more obvious and general case that demonstrates the bug, reopens it, and assigns it to the Programmer to fix. The programmer fixes the bg, resolves it as fixed, and assign it to the Tester. The tester confirms the fix and closes the bug.

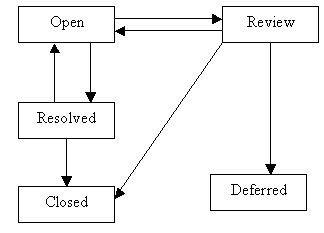

You can see that a bug might undergo numerous changes and iterations over its life, sometimes looping back and starting the life all over again. Figure below takes the simple model above and adds to it possible decisions, approvals, and looping that can occur in most projects. Of course every software company and project will have its own system, but this figure is fairly generic and should cover most any bug life cycle that you’ll encounter

The generic life cycle has two additional states and extra connecting lines. The review state is where Project Manager or the committee, sometimes called a change Control Board, decides whether the bug should be fixed. In some projects all bugs go through the review state before they’re assigned to the programmer for fixing. In other projects, this may not occur until near the end of the project, or not at all. Notice that the review state can also go directly to the closed state. This happens if the review decides that the bug shouldn’t be fixed – it could be too minor is really not a problem, or is a testing error. The other is a deferred. The review may determine that the bug should be considered for fixing at sometime in the future, but not for this release of the software. The additional line from resolved state back to the open state covers the situation where the tester finds that the bug hasn’t been fixed. It gets reopened and the bugs life cycle repeats. The two dotted lines that loop from the closed and the deferred state back to the open state rarely occur but are important enough to mention. Since a Tester never gives up, its possible that a bug was thought to be fixed, tested and closed could reappear. Such bugs are often called Regressions. It’s possible that a deferred bug could later be proven serious enough to fix immediately. If either of these occurs, the bug is reopened and started through the process again. Most Project teams adopt rules for who can change the state of a bug or assign it to someone else.For example, maybe only the Project Manager can decide to defer a bug or only a tester is permitted to close a bug. What’s important is that once you log a bug, you follow it through its life cycle, don’t lose track of it, and prove the necessary information to drive it to being fixed and closed. Bug Report - Why

Edited by poli - 05May2007 at 6:00am Post Resume: Click here to Upload your Resume & Apply for Jobs |

|

IP Logged IP Logged |

|

|

||

Forum Jump |

You cannot post new topics in this forum You cannot reply to topics in this forum You cannot delete your posts in this forum You cannot edit your posts in this forum You cannot create polls in this forum You cannot vote in polls in this forum |

|

© Vyom Technosoft Pvt. Ltd. All Rights Reserved.